Best Books on Writing: A Series, Part 1

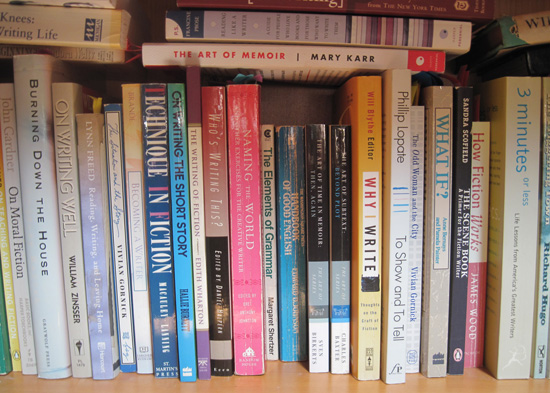

I get a little weary just thinking about books on writing, especially the “how to” variety. There are so many out there–books on how to become a writer, books on how to structure a story or novel, books on how to create interesting characters, books on motivating yourself to write and overcoming obstacles, and–my favourite–books on how to make a million bucks as a writer.

Most of them are unreadable. They make you not want to write.

How many times have I browsed the writing section in the actual places that were once known as bookstores, opened one, and found myself drifting off to sleep in the vertical position. As a general rule, they tend to be either boring and dry, or too reliant on reductive formulas for constructing plots or creating interesting characters.

Really, there are no formulas for writing any kind of fiction but the most cliched; and any book that purports to teach you how to write well, ought to be interesting, itself, to read. Any really good book on writing should make you want to write, and give you some good tips along the way.

But thankfully, there are some very good books on writing, and the good ones don’t tell you how to write so much as tell you what took place when an author wrote something wonderful. What are the components, the characteristics, the ingredients of great writing? This (it just so happens) is also what my workshop is about. And there are other interesting and useful ways to write about writing, i.e. about the process, issues of style, and the writing life itself. These kind of books can be of great interest.

In my recommendations, I’m going to ignore the three books most often cited in these kind of lists, i.e. the ones by Stephen King, Anne Lamott, and Natalie Goldberg. Everyone already seems to know about them, they don’t need any further promotion.

The books I am recommending, are here because I found them fascinating to read, provocative, and because they offer considerable insight into the act and art of writing. Some are classics, others barely known and hence deserving of more attention.

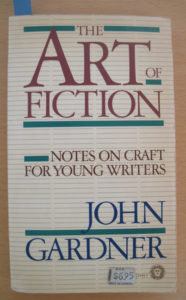

THE ART OF FICTION by John Gardner

THE ART OF FICTION by John Gardner

This is a classic. I consider it to be the best book I’ve read on writing; but it’s also a book near and dear to my heart, as I was first introduced to it by Barbara Gowdy, in the incredible workshop I took with her in the 90s. Gowdy used prompts from this book and many of the larger concepts in it informed her teaching. Gardner and Gowdy’s workshop, in turn, formed much of the basis of my workshop.

Along with being a great novelist, Gardner was the most influential writing teacher of the 1980s. He understands what makes great literature great, and can convey that to aspiring writers in comprehensible language and sentences as beautiful and succinct as the ones he writes about. There are sections in this book I have read aloud in workshop for some 25 years, and I never tire of them. I am struck again and again by how profound his grasp of the mechanics of writing and story-telling are, how much he has to offer anyone wanting a thorough exploration of every aspect of the craft, and how broad an understanding he has of literature from the ancients to the classics to the contemporary. And all of this in highly entertaining, perfectly sculpted prose.

Chapter headings alone set this book apart: “Aesthetic Law and Artistic Mystery,” Basic Skills, Genre, and Fiction as Dream,” “Interest and Truth.” You already know you are in for revelation. Two of his more far-reaching concepts–Fiction as Dream and Authenticating Details–actually changed the way I thought about literature, writing, and teaching writing. Just now I open the book at andom and find a sentence like this: “If Lois Lane and Superman were to wander into a scene by Henry James what would they think of it and how would they affect it?” Just trying that on for 10 seconds makes my brain expand in fun and uncomfortable ways.

One caveat: parts of this book may be hard to grasp by anyone who does not have a considerable amount of serious reading behind them. But other sections should be accessible to anyone.

NAMING THE WORLD edited by Bret Anthony Johnston

NAMING THE WORLD edited by Bret Anthony Johnston

This is a wonderfully rich collection of mini lectures/explications/discussions on every aspect of the craft, by dozens of eminent authors, each with a relevant prompt at the end. The prompts are very good, and the workshop lectures even better–with chapters covering such well worn subjects as character, point of view, tone, plot and narrative, dialogue and voice, descriptive language, revision, etc., yet all of it seems fresh.

The great appeal and interest of this book comes from its wealth of subjects, explored by so many very different and highly accomplished authors, i.e. it’s not one woman telling you how she writes or how she thinks you should write. And the subjects themselves are so enticing and juicy: i.e. “Destroying What you Love,” “The Monster in the Attic,” “Learning to Lie,” “What do You Want Most in Life?” “Your Five Seconds of Shame!” and “Writing Sex Scenes.” Reading this book, you will want to read on, and by the time you have worked your way through even half of it, you will know way more about writing than when you started it. With any luck, you will also be full of new ideas and your writing will improve.

Share

A Few Hateful Things

It can be very cathartic to write about things you hate–and even gratifying for others to read, provided your bitching is funny, righteous and inspiring. Complaining has a bad rep in this Canadian, mainly Protestant society, (even they protested once) but it’s a fact that nothing in the world ever improved because people kept their mouths shut.

There is even a literary precedent for bitching at length, in the wonderful Pillow Book of Sei Shonagon, a 10th Century Japanese courtesan who kept lists of her likes and dislikes in her journal. Some contemporary bloggers (a word I hate) have pointed to Shonagon as the world’s first blogger, as The Pillow Book is the kind of seemingly random collection of musings and jottings on different topics that characterizes many of today’s blogs.

The particular list that inspired me here is called “Hateful Things,” and–as well as being in The Pillow Book–is also included in the definitive creative nonfiction anthology I tell all my students to read, The Art of the Personal Essay, edited by Philip Lopate.

Almost none of them bother to read it though.

I hate that.

So, having established a literary precedent, a few Hateful Things:

Toilet paper dispensers that do not give up their bounty easily. Isn’t life already hard enough without having to fight for a few precious scraps of one-ply? I’m referring to the kind of dispenser one typically sees in cheap restaurants, hospitals, and low end public pissoirs. Gently now, you have to tug at the tiny bit of tissue so delicately (like a surgeon, really) lest it break off and leave you with just one measly square, not enough to wipe a fly’s behind. If you are really talented you may just get four squares out of its greedy maw–always serrated with those shark-like microscopic teeth–before the inevitable breakage. And yes, they are serrated for tearing the TP, but also, I am convinced, to discourage volume-deprived users like myself from attempting to insert their fingers into the dispenser to get the tissue they need and deserve.

* * *

I notice, particularly when making small purchases, that “perfect” is replacing “awesome.” Really, it’s less than perfect–but marginally preferable to awesome, which was the worst ever, and a word I waged a tireless and mainly futile campaign against. Some of my students got called on it. Some got cured, but others retaliated by saying it even more.

I have to confess that my hatred of the ubiquitous “awesome” was so great that I once walked out of a shoe store because I was hearing it too much. (They also had no shoes I wanted.) For me, the world was now divided into two halves: people who said “awesome” and people who did not. This binary system eventually broke down when a friend who did not say “awesome” turned out to be an ass, and someone else who did say “awesome” proved to be a loyal friend.

So now it’s “perfect.” “Perfect” may be slightly better than “awesome” but why not just “thanks!” or “fine!” or “yes, let’s do that” or–if you absolutely have to exaggerate your enthusiasm over the most mundane transactions or plans–then “great!” when someone pays for an apple, or suggests going to lunch. Maybe you are genuinely thrilled by something, in which case “amazing” will do. If you want to try something really retro, say “super.” Either it will impress as some new strain of hipster irony or you’ll get laughed at.

But why this need to exhibit such an excess of enthusiasm over nothing? It is not “awesome” that I just handed you a debit card to pay for my latest purchase; it is not “perfect” that we are going to lunch on the 12th–unless we are going to fall in love over tacos and move to your hacienda in Mexico together.

Likewise, truly “awesome” would be flying over the Arctic at sunrise, or watching the aurora borealis on your back in a fiord in Norway, lying next to Joanna Lumley. Afterwards, your vodka martini in the ice hotel might be perfect.

And it’s not like I hate or resist every new expression that enters the language. I was fine with “Oh. My. God.” and actually liked “How sad is that?”

* * *

Needing gas urgently–the need gas bad light has been on for many kilometers now, and one never knows exactly how far one can go on fumes, and pulling into the only station for miles (“kilometers” won’t work in this context, and while I’m digressing–what the hell happened to all the gas stations in the city?) and seeing there’s a huge mosh pit of giant unwieldy SUVs scattered helter skelter around the pumps; no-one clear on what line they’re in or even what direction they’re not moving in; some parked in order to amble in to the inappropriately named hasty market to get coffee; another vehicle coming in tight behind you, effectively locking you into this confused maze of gas-hungry behemoth vehicles for hours, maybe days; you running out of gas before you even reach the pumps, you might even die here.

* * *

The price of parsley at my local, independent, previously immigrant based and affordable, now yuppie pandering supermarket: $3.

As John McEnroe once famously said : “You cannot be serious!”

Last year they tried out $8 cauliflower on us, as in Care to buy this, suckers? We did not, and now cauliflower is back to $4 a cerebral head. (I have always found its resemblance to a brain kind of freaky.) So crank up the parsley. See what we’ll pay. The parking lot is full of Benzs, so who knows …

* * *

The Really Ugly Malignant Pimple. You know who.

* * *

Share

The Small Beautiful Thing Instead of the Enormous Terrible Thing

Lucia Berlin: A Manual For Cleaning Women

My third post has been a bitch. Every time I set out to write about my chosen topic, a giant bogeyman with an absurd comb over invades my brain and hijacks the post. I’m now on my fourth or fifth attempt and I am determined! Still, the inner conflict of what to write about persists: an incredibly powerful and original book of stories by a brilliant and fearless woman–largely overlooked in her own lifetime–or, the most disgusting and dangerous election outcome in U.S. history?

The conflict itself is so interesting, it wants to become the subject. I must resist that too.

Since opening A Manual for Cleaning Women over a month ago, I had wanted to post on it. But then came the Great Catastrophe on November 8, and since then I have dwelt obsessively on the Truly Repugnant, Unthinkable Man President. I always tell students to write about what obsesses them, and I–like so many now in these dark times–am almost pathologically obsessed.

And how can one write about a mere book, in the face of the enormity of what has just transpired?

But no, I will write about Berlin (Trump is actually of German descent, but lied and said his ancestors were Swedish! How clever of him) the small beautiful thing, instead of the enormous terrible thing.

* * *

During my MFA at Bennington, I remember a teacher once saying a story should hit you in the solar plexus. (Don’t even ask what or where the solar plexus is, just trust that it’s crucial and highly sensitive.)

Berlin’s stories hit me in the solar plexus: they’re heavy and intense and unforgettable and after reading one you just want to put the book down for awhile and let the vapours linger. You don’t want anything–not another story or even a human voice–disturbing the immediate aftermath until you’ve absorbed and relished its full impact.

You may also need a drink before you pick up the book again. The best stories in this collection–and there are many–all leave you feeling like you’ve been through something major, and you survived.

That last line sounds a lot like Berlin’s life. She was born in 1936, lived an itinerant life in Alaska, Chile, Mexico, the American Southwest, NYC and Los Angeles. She came from an abusive home, had a lifelong struggle with scoliosis (a painful spinal condition) and alcoholism, three failed marriages (two to jazz musicians with addictions) and four sons whom she raised as a single mother– supporting them through a series of lowly jobs as a switchboard operator, ER attendant, and cleaning woman. And throughout it all she wrote: from the 70s through the 90s, she published seventy-six short stories in small presses, which went largely unnoticed. By the 1990s she was sober and writing steadily, and became an associate professor at the University of Colorado. The scoliosis ultimately caused her health to fail, and she died in 2004 in California.

An extremely hard life, to say the least, but writer’s gold, and Berlin mined every ounce of it. Publication this time around–in 2015, eleven years after her death–set off a loud buzz in all the right places, eventually landing A Manual for Cleaning Women on the New York Times best-seller list. Comparisons have been made to Chekhov (her hero), Raymond Carver, and Denis Johnson, among others. Chekhov is a lofty comparison; he is widely considered to be the greatest short story writer of all time. She will never equal Chekhov in output (he wrote close to 300 stories, many of them as long as novellas) but reading her stories, I sometimes sense his presence in the room. They’re that good.

The 43 stories collected in A Manual for Cleaning Women represent her best writing from the 80s and 90s and are very short, mainly 1rst person vignettes taken directly from her life. They’re set in laundromats, detox wards, emergency rooms, Mexican abortion clinics and cheap hotels; and are populated by drunks, beautiful losers, radical nuns, crazed dentists, and bohemians, along with everyday people caught up in the snares of the human condition.

There is so much worthy of comment in these stories, but I think what astonished and impressed me most was the complete lack of self pity, or bitterness in her writing. Regardless of how grim, difficult or hopeless the circumstance, it is all told as a great adventure, with an easy candour and a wonderful gallows humour. I have no idea how she achieved this perspective, and I can’t recall ever reading such harrowing autobiographical stories so free of any traces of victimization, blame or remorse.

Properly, I would need at least another 1,000 words to do these stories justice, but I want to keep it brief. So I will let others sum it up for me. Here’s Stephen Emerson in the book’s Introduction:

“Lucia’s writing has got snap. When I think of it, I sometimes imagine a master drummer in motion behind a large trap set, striking ambidextrously at an array of snares, tom-toms, and ride cymbals while working the pedals with both feet.

It isn’t that the work is percussive, it’s just that there’s so much going on.

The prose claws its way off the page. It has vitality. It reveals.”

And Lydia Davis–a favourite writer of mine who corresponded with Berlin for 30 years but never actually met her–in the book’s Forward:

“Lucia Berlin’s stories are electric, they buzz and crackle as the live wires touch. And in response, the reader’s mind, too, beguiled, enraptured, comes alive, all synapses firing. This is the way we like to be, when we’re reading–using our brain, feeling our hearts beat.”

Share

Fourteen Great Reasons to Write

For revenge

To set the record straight

There’s a story that wants to be told

Because you love seeing words form into sentences, and sentences form into paragraphs…

Because you get actual pleasure from describing just one thing perfectly

To understand who you are and everything (or one thing) that happened to you

Because there’s nothing on TV

To purge your demons

To befriend your demons

Because you enjoy punctuation

To find out what you think

Because it’s fun to do

Because once it stopped being fun to do it became torment and you like torment

Because it’s a challenge

Share

The Blog Introduces and Justifies Herself

For years many people told me that I should write a blog, and I always answered that I couldn’t be blothered.

There was just so much flotsam and jetsam already online–so many many words written by so many, many people that no-one had the time or interest to read, that I felt it almost my duty not to contribute to the excess.

And how many of them were interesting?

Mine would be, of course, but the idea of getting buried in that heap …

So why now? (I feel I have to justify myself.)

Well, for one thing, people have finally stopped telling me to write a blog. So maybe I just will!

But also, I just found out that a blog can do great things for your SEO–the holy grail for anyone whose livelihood depends on being found on the net. And then you can put twitter next to your blog and they’ll make beautiful SEO music together, and you’ll be just like the cashier at the pricey organic grocery store in my yuppie overrun neighbourhood who intoned with great zeal to the person in front of me in line, “You can follow our sausage on Twitter!”

Anyway, the blog. Hopefully it will give prospective students still more info on what yours truly and her workshops are about; and for repeat students, more talk about books and writing to keep you inspired and reading and writing.

And for myself, a place to unload my ongoing thoughts on writing, literature, and whatever else is delighting or infuriating or baffling me at the moment.

Because that’s why most of us write, really.

To get it out of ourselves, and into someone else, via the screen, the page, whatever.